Colour Theory for Photographers: A Practical Guide

Colour theory for photographers is something I never thought about when I first started out.

Share the Love This Valentine’s Day – 25% Off

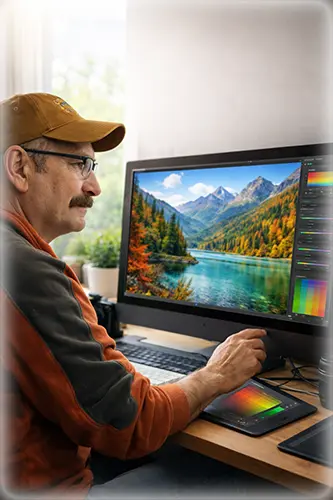

As we get older, our colour vision changes, and the result affects our life, including photography. Our eyes and brains work together to turn light into colour, but this process becomes less precise with age. Research shows that older adults often struggle to see certain colours, especially blues and subtle tones. Colours can appear less vibrant, which can affect how we as photographers see, edit, and capture colour in our photos.

These changes happen slowly and are easy to miss. The camera still works. The monitor still looks fine. Yet the final image may not appear the same to other people. Understanding how aging eyes affect colour perception helps us as photographers to edit more confidently and consistently. It does not limit creativity. It adds awareness.

As we get older, several parts of the eye change. These changes affect how colour and brightness are seen.

The clear lens inside the eye thickens over time. It also becomes slightly yellow. This filters the light before it reaches the retina. Blue light is affected the most, which changes how cool colours appear.

The pupil also becomes smaller. Less light enters the eye. This can make images look darker and flatter than they really are.

The retina becomes less sensitive to contrast. Fine colour differences are harder to detect. Shadows can lose detail. Highlights may feel harsh.

These changes often begin in the 40s and become more noticeable after 50. They are a normal part of aging and do not mean your eyesight is failing.

Colour plays a large role in photography. It sets mood, suggests time of day, and guides the viewer’s eye. When colour perception shifts, editing decisions shift as well.

The most common issue for aging photographers is oversaturation. Because colours appear less intense, photographers often increase saturation without realizing it. On their own screen, the image looks balanced. On other screens, it can look too strong.

Blues, teals, and purples are often pushed the most. Skies may look heavy. Water can feel unnatural. Forest greens may lose depth.

This does not happen all at once. It builds slowly, which makes it harder to notice.

Many photographers calibrate their monitors and assume colour issues are solved. Calibration is important. It ensures the monitor displays colour accurately.

However, calibration cannot correct how your eyes interpret colour. Two people can look at the same calibrated screen and see different things.

If your eyes filter blue light more than they used to, a calibrated monitor will still appear warmer to you. You may add more blue to compensate.

Calibration supports accuracy, but it does not replace awareness.

Looking to stretch your budget? We’ve got good news! Use the SPECIAL code whosaid15 for an extra 5% off

The brain adapts to what it sees. This helps us function in different lighting conditions. In photo editing, this adaptation can cause problems.

During long editing sessions, your eyes and brain adjust to strong colours. What looked bold at first can start to look normal. This makes it easy to keep pushing colour without noticing.

As colour sensitivity declines with age, this effect becomes stronger.

Many photographers over 50 notice patterns in their edits once they look closely. These patterns are not about skill. They are about perception.

Common issues include overly saturated skies, strong teal or aqua tones, heavy greens in forest scenes, warm skin tones pushed too far, and loss of subtle colour transitions.

These images often look fine to the photographer but appear intense to others.

| Age-Related Vision Change | What the Photographer Sees | Common Editing Response | Better Editing Habit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lens yellowing | Colours look muted | Increase saturation | Lower saturation slightly |

| Reduced blue sensitivity | Skies look dull | Push blues and teals | Use reference images |

| Lower contrast sensitivity | Image feels flat | Add heavy contrast | Adjust contrast slowly |

| Smaller pupil size | Image looks dark | Brighten midtones | Check histogram balance |

| Visual fatigue | Colours feel normal | Keep pushing edits | Take editing breaks |

| Neural colour decline | Subtle tones vanish | Over-edit hues | Focus on light first |

Aging eyes are not a limitation in photography. They are a reminder to slow down, check your work, and trust the process

...Bob

You do not need to change your style or tools. A few small habits can improve colour balance.

Lower saturation as a final check. After editing, reduce global saturation slightly. If the image still works, your original edit was likely too strong.

Edit in short sessions. Limit sessions to 30 or 45 minutes. Step away and return later. Fresh eyes reveal issues quickly.

Use trusted reference images. Compare your work to images you trust. This gives your eyes a neutral point.

Check on multiple screens. View your image on a phone or tablet. Differences become obvious.

Strong photos depend on light, contrast, and structure. Colour should support these elements.

Start by adjusting exposure and tone. Make sure the image works in black and white. Once the structure is solid, add colour with care.

This approach reduces the urge to rely on saturation.

Editing tools can help confirm what your eyes may miss. Histograms show tonal balance without relying on colour perception.

Selective colour adjustments are safer than global changes. Adjust specific hues instead of everything at once.

Be careful with presets. Many are designed for impact, not accuracy. Use them as a starting point, not a final look.

Your audience includes people of many ages. Younger viewers often see colour more strongly. What feels balanced to you may feel intense to them.

Editing with this in mind helps your images connect with more people. It does not mean editing for others. It means being aware of differences.

Aging eyes do not make you a worse photographer. Experience often improves patience, composition, and storytelling.

Many photographers create their best work later in life. Awareness of colour perception helps protect that progress.

Regular eye exams help maintain comfort and clarity. Updated prescriptions reduce strain.

Good workspace lighting matters. Avoid strong colour casts in room lighting. Neutral light supports better editing decisions.

If you use reading glasses, consider a pair designed for screen distance.

Photography should remain enjoyable. Awareness of colour perception is a tool, not a limitation.

Natural colour ages well. It holds up across screens and time. Small adjustments help your work stay honest.

Aging eyes are part of life. They change slowly and quietly. In photography, these changes affect colour perception, not creativity.

With awareness and a few simple habits, you can keep editing with confidence. Your experience and love for photography matter more than ever.

Your eyes may change. Your vision as a photographer does not.

Yes. As eyes age, their colour sensitivity decreases, especially in blues and cool tones. This makes colours appear less vibrant, and it can affect how photographers judge saturation and colour balance when editing photos.

Older photographers may oversaturate images because colours appear muted in aging eyes. Increasing saturation makes the image look correct to them, but it can appear too strong to others viewing the photo.

No. Monitor calibration ensures accurate colour displays, but it cannot change how eyes perceive colour. Aging photographers should also use reference images and view edits on multiple screens to maintain balance.

Colour theory for photographers is something I never thought about when I first started out.

I think steel wool photography creates some of the most amazing images you can capture

Long exposure photography is a technique that uses slow shutter speeds to capture silky smooth